An understanding of corporate insolvency rules in countries where they have an interest should be a priority for investors, especially given the extent to which pandemic support measures have affected corporate insolvency rates

by Paul Golden

When a company can no longer meet its financial obligations to lenders as debts become due, it is insolvent. Whether assets exceed liabilities is generally deemed less important, since many corporates have balance sheets that are not solvent but have the cash flow to remain solvent. But what does insolvency mean today, in a world where companies unable to meet their commitments are kept afloat through public money, government guarantees and the like?

Credit insurance company Euler Hermes predicted, in its Global insolvency outlook 2020, published in January of that year, that global business failures would increase by 6% year-on-year in 2020, the fourth consecutive year of rises, with the largest increases expected in Chile (+21%), Slovakia (+12%), China and Singapore (both +10%).

Within a matter of weeks, these forecasts went out of the window as Covid-19 took hold. Euler Hermes’ 2021–2022: Vaccine economics, published in December 2020, notes that widespread government support in 2020, and its extension into 2021, has kept insolvencies artificially low. However, the phasing out of support will lead to “an increase in insolvencies as early as H2 2021”.

Uneven initial conditions pre-pandemic, and differing strategies to tackle the virus, mean that different countries and regions are expected to see asymmetric insolvency trajectories. North America is predicted to see the most significant rise (57% by the end of 2022 compared to 2019), while for Western Europe and Asia the figure stands at 23% and 18% growth respectively.

Global insolvency and the pandemic

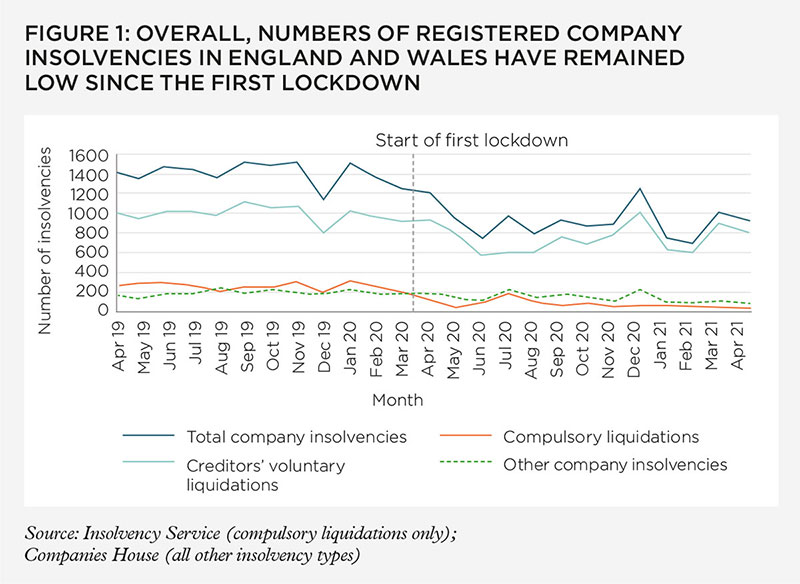

The global insolvency landscape has been massively skewed by unprecedented government support for businesses affected by the pandemic (see our previous special report on the great global recapitalisation). According to statistics from the UK’s Insolvency Service, the number of registered company insolvencies in England and Wales in January 2021 was 752, approximately half the number for the same month in 2020 (1,515), and in February 2021 the number was 686, 49% lower than 2020. By April 2021, this figure had increased, but the 925 registered was still 23% lower than in April 2020. In the US, the American Bankruptcy Institute reports that commercial bankruptcy filings in February 2021 were 37% lower than in February 2020, but only 10% lower year-on-year in April 2021.

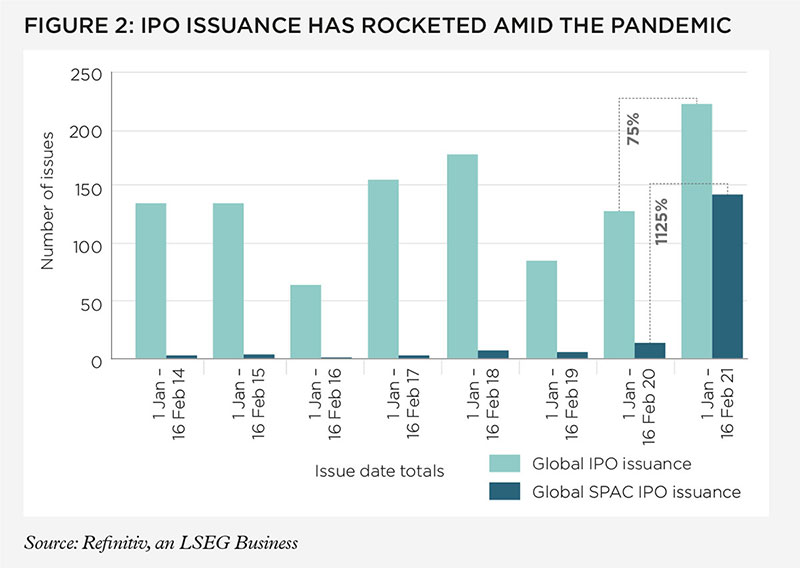

Companies have also embarked on a frenzy of corporate fundraising. Data from Refinitiv, shared with The Review, shows that global corporate initial public offering (IPO) issuances between 1 January and 16 February 2021 raised almost US$57bn – an increase of 218% on the same period in 2020. IPO issuance by special purpose acquisition companies (shell corporations designed to take companies public without going through the traditional IPO process) went through the roof in the first six weeks of 2021, with the US$43.4bn raised from 147 issuances representing value growth of 1,540% and issue numbers growth of 1,125% compared to the first six weeks of 2020 (see Figure 2).

Investors and insolvency

Insolvency regimes around the world either follow a debtor in a possession-type regime, where the company is in control to a very large degree (such as in the US), or they favour the creditor, which is the case in many of the English law countries where directors must take all steps to protect the interests of creditors, explains Andrew Wollaston, global leader for reshaping results, turnaround and restructuring strategy at EY.

As for what this means for investors, Blair Nimmo, CEO of Interpath Advisory, which was formed in May after KPMG sold its UK Restructuring practice to a new company backed by H.I.G. Capital, says mid-market corporates are carrying a lot of tax-related debt on their balance sheets and that it will take some up to five years of trading just to pay back these debts. He suggests that the UK’s approach to insolvency is more efficient and that there are aspects of the US regime that merely serve to prop up poorly performing companies. “You might think it is positive that the US is more company-friendly, but you have to consider the creditors – you need creditors in an economy to keep money flowing,” says Blair.

Investors need to understand all possible downside risks for any investment. In this context, David Soden, a partner in the restructuring practice at Deloitte who specialises in corporate recovery, says that it’s critical to consider the insolvency legislation of any market they are looking to invest in.

"When lockdowns are over there will be opportunities to invest in businesses that are ongoing but need investment to turn themselves around"

Fellow Deloitte partner Phil Reynolds, who heads up the firm’s Canadian national restructuring team, says that not every developing country even has a reorganisation regime. “Some have a straight liquidation regime and others are not completely transparent,” he adds. “There are reorganisations in South America that started ten years ago and are still ongoing. If I were an investor in that scenario, I would have written off my investment nine years ago.”

However, investors can apply for proceedings in countries where they are more familiar with the corporate insolvency regime. “In developed countries, most of the statutes state that reorganisation should take place where the corporate is headquartered, but that is not the case everywhere,” says David.

Alison Goldthorp, partner at global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright, agrees that investors should familiarise themselves with local insolvency legislation as part of their due diligence, partly because they need to know how they would seek to collect debts to the company they have invested in. “When lockdowns are over there will be opportunities to invest in businesses that are ongoing but need investment to turn themselves around,” she continues.

Creditor changes

One of the interesting aspects of UK state support for companies impacted by Covid-19 is that the restriction on winding up petitions that came into force in June 2020 placed the onus on the creditor to prove to the court that the debtor business had not suffered financially as a result of the pandemic.

A significant change is that HMRC has regained its preferential creditor status, a move which business groups, including R3 (the insolvency and restructuring trade body), were against, as they consider it a threat to business lending and business rescue. “This means that for all insolvency appointments after 1 December 2020, all taxes held by businesses that have been paid by employees (PAYE/employees NIC/CIS/loan repayments) and customers (VAT) will be paid immediately after the current preferential arrears of wages and holiday pay preferential creditors,” explains Jeremy Boyle, managing partner and head of insolvency at specialist corporate insolvency law firm Summit Law.

In the UK, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, described by the government as the largest change to the corporate insolvency regime in more than two decades, came into force on 26 June 2020. The Act contains a number of temporary provisions, consisting of modifications to corporate insolvency law and company law to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. Its key provisions include the introduction of a 20-day corporate moratorium, giving businesses protection from creditor action while they seek professional restructuring advice, and a new restructuring plan that has the ability to bind creditors to it. The UK government has extended the expiry date of the Act to end of April 2022.

Insolvency can be one of the most effective ways of restructuring a company

According to figures from the UK’s Insolvency Service, four companies obtained a moratorium and five companies had a restructuring plan sanctioned by a court between 26 June 2020 and 28 February 2021. The Insolvency Service notes that the “low number of cases of each of these new legislative tools since the Act came into force is likely to be as a result of the range of government support provided to companies” over the past year.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Act is that if one creditor class approves a restructuring plan, a court can be asked to sanction it, even if the other credit classes are not in agreement. “This is called a ‘cross-class cram down’,” explains Alison. “It has been an option in the US for a number of years but has only recently been available in Europe. Since the focus of these procedures is on keeping the company going and therefore keeping value in the equity, they are really important for existing investors.”

On the question of whether corporate law across developed and emerging economies is sufficiently robust to deal with a potentially sharp increase in insolvency rates, Ed Macnamara, global leader for restructuring and insolvency at PwC, notes that there are many jurisdictions where the number of professionals capable of handling insolvencies and the capacity of the judiciary is severely limited.

“The World Bank’s insolvency and debt resolution team assists governments in improving their credit environments through the development of more effective insolvency systems,” he says. “Part of these efforts has been to move countries away from a liquidation-focused outcome and create a ‘rescue culture’.”

While the forecasted sharp increase in insolvency rates will be bad news for many, it should be acknowledged that the current corporate environment presents opportunities for investment professionals.

With interest rates at record lows, there is plenty of money looking for a home, and diligent management teams have taken a lot of costs out of their businesses, while using the lessons learnt from the 2008 global financial crisis to hone their skills in terms of forecasting, working capital control, and cash preservation. Insolvency can be one of the most effective ways of restructuring a company, and diligent investors should be on their toes to take advantage of the openings that will inevitably come their way.

The full article was originally published in the June 2021 edition of The Review.

The flipbook edition is now available online for all members.

All CISI members, excluding student members, are eligible to receive a hard copy of the quarterly print edition of the magazine. Members can opt in to receive the print edition by logging in to MyCISI, clicking on My account, then clicking the Communications tab and selecting ‘Yes’.

Once you have read the print edition, keep coming back to the digital edition of The Review, which is updated regularly with news, features and comment about the Institute and the financial services sector